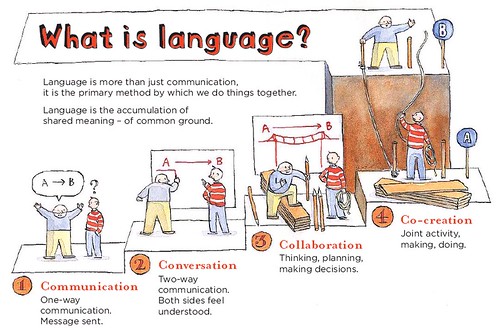

Before we ask what visual language is, it makes sense to ask what language is. Here’s an attempt to visualize some current thinking on language. The image below summarizes my synthesis of some ideas from a book called Using Language by Herbert H. Clark.

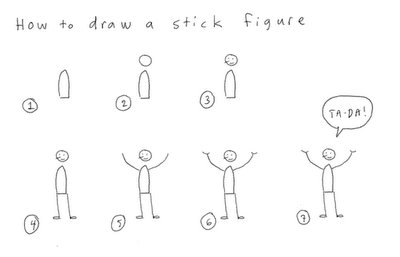

How to draw a stick figure

Cliff Atkinson asked if I would show how to draw a stick figure, so I decided to let you in on a little trade secret: All stick figures are not created equal. Today I’m going to teach you to draw a stick figure the way we do it at XPLANE.

Cliff Atkinson asked if I would show how to draw a stick figure, so I decided to let you in on a little trade secret: All stick figures are not created equal. Today I’m going to teach you to draw a stick figure the way we do it at XPLANE.

Stick figures are a quick and easy way to visually represent the human body doing just about anything. I’m going to start you off easy by showing you how to draw a simple standing figure.

Here’s a larger image of the drawing above.

1. Most people start a stick figure by drawing the head. This is a mistake. Since a stick figure represents the whole person, the best way to draw it is the way you see a whole person. Think about what you notice first when seeing someone from a distance. Always start with the body. The body is the center of gravity and motion. By starting with the body you will capture the essence of the gesture you want to convey.

2. After you have drawn the body in the position that you want, draw in a circle for the head. The placement of the head in relation to the body is essential. Happiness, angst, speed and sluggishness can all be conveyed by the relative positions of the head and body. Observe people doing their daily routines and you’ll see what I mean.

3. Next, draw the facial expression. Your basic smiley face or frowney face will work here just fine. Adding a little line for a nose will help you show which direction the head is pointing. This can be especially important when you want to show two people interacting with each other.

4. Add the legs next — they are more essential to conveying the gesture than the arms. When my basketball coach taught me to shoot, he explained that the primary energy that propels the ball comes not from your arms but from your legs (Watch some basketball on TV and you can actually see this). The energy of a stick figure works the same way. Note the use of small ovals to represent feet. This helps connect the person to the imaginary ground.

5. Now draw the arms, and complete the gesture you started with the legs.

6. I made the hands a separate step so you could see what a difference a couple of little lines makes. A short, one-line stroke will suffice for nearly any gesture.

7. Of course you’re drawing the stick figure to convey some idea, action or emotion. Thought bubbles and word balloons are a great way to round out the complete thought.

Now that you’ve drawn a standing person, try your hand at some more tricky problems:

– How would you draw a tall person? A fat person? Someone with long hair or a beard?

– Go to a public place and see if you can capture the gestures of the people around you in stick-figure drawings. This is a great way to hone your observation skills.

– See if you can draw people running, dancing, fighting and sitting.

– Here’s a hard one: draw a stick figure riding a bike.

Please send me a link to your drawings so I can share your successes!

What’s next in visual communication?

This article was originally published in Infonomia, a Spanish magazine. Read it in Spanish here.

This article was originally published in Infonomia, a Spanish magazine. Read it in Spanish here.

Two million years ago, the first distinct and recognizably human cultures emerged. These early humans – known as Homo Erectus, or upright man – made and used complex tools, formed societies, migrated over long distances, used fire, and cooked food – and they did all that without words.

These early humans had 80% of the brain capacity of modern humans, and yet they were biologically incapable of speech. They communicated with each other visually, through gestures, observation and mimicry.

It wasn’t until much later – 25,000 years ago – that the first evidence of advanced drawing and painting skills appears, in cave paintings, such as the beautiful and famous examples at Altamira in northern Spain.

Then, 6,000 years ago, writing appears. Paper was invented by an administrator (anyone surprised by that?) about 4,000 years later.

The combination of writing and paper made it possible to share complex information over long distances. For example, explorers could make and share maps, sketches and detailed records of their discoveries.

In 1440 the publishing industry was born when Johannes Gutenberg invented the printing press. For the first time, written works could be mass-produced. Books became cheaply available.

With the printing press, words were much easier to reproduce than images: roughly 100 alphanumeric characters can convey nearly any idea, whereas every visual image must be uniquely created. There were other restrictions as well: words must be carefully set in lines and columns. Occasionally images could be inset to illustrate the text but all had to be carefully positioned according to a grid.

The printing press gave birth to a powerful industry. Monarchies crumbled as the voice of the people, through pamphlets and tracts, could now compete with the voices of priests, kings and queens. The industrial age of publishing reached its peak with the massive, global entertainment industry in the late 20th century.

Today, entertainment giants such as Fox, Viacom, Disney and Sony dominate global culture because they control most of what the world sees and hears. This in turn gives them tremendous influence over what the world thinks and feels. But their days are numbered, and they know it. In the 21st century, and communication has entered a digital age. Publishing power, like computing power, gets cheaper and cheaper all the time. Eventually, both computing and publishing power will be as cheap and plentiful as paper is today.

It started in 1984, when Apple introduced the Macintosh computer and the first graphical user interface (GUI). For the first time, ordinary people could interact with a computer visually: with window, icons, folders, trash bins. People who had never considered themselves “computer people” now had access to a powerful tool for creative endeavors, which allowed them to do things they could never have done before.

Individuals could now become publishers. With very little investment they could design their own business cards, brochures, logos, even magazines. It was called desktop publishing, and professional publishers were horrified.

The world will never be the same, they said. Without professional training, people will abuse this power. And they were right. Bad design proliferated. Badly designed logos, badly designed brochures, badly designed newsletters, badly designed magazines, became the norm, when once they had been the exception.

Publishing involves both the creation and delivery of information. The desktop publishing revolution solved the creation problem, but in 1984, to deliver a magazine you still needed to print it and mail it, and to deliver a video you needed to broadcast it. And those things were expensive.

But in 1991, Tim Berners-Lee invented another revolution in visual communication: the web browser. Today, because of the web browser, you can publish your ideas to the world for the price of an internet connection.

The cost of creating and publishing information is plummeting inexorably towards zero.

The publishing industry has counted on people’s laziness, their willingness to be led, and their willingness to be fed information. This is the same mistake that established authorities have made since the beginning of time.

They fail to realize a critical fact: the ability to play with tools drives literacy, and the more literate people are, the more involved they become.

Children play with paper and pencils in order to learn how to draw and spell. And as people played with their computers they began to develop their visual communication skills. And playing with digital communication tools like the internet drives visual literacy.

Today, we are free once more. Paradoxically, now that everything has been reduced to zeros and ones, our only limit is our imagination. What’s interesting is that we continue to constrain ourselves to the grid, even when it is no longer necessary. The conventions of printing, which once liberated ideas by making them mass-producible, have now become a prison.

So what’s next? Watch the kids. In the 1970s we started playing video games, and although we didn’t know it at the time, we were learning how to interact with digital technologies. We were learning the hand-eye coordination skills we would need to operate the computers of the 1980s.

The toys of today are the tools of tomorrow: blogging, podcasting, photosharing, videoblogging – these are all early indicators. People are making their own movies and publishing their ideas to the world. With every passing year the technology gets cheaper and easier to use.

What we are seeing today on the internet is the emergence of a truly global culture, a culture that communicates visually. People around the world are playing with visual thinking toys, and their visual literacy is slowly rising.

We’re in the process of learning how to communicate visually – we’re witnessing the emergence of a global visual language. I am very happy to be a part of it.

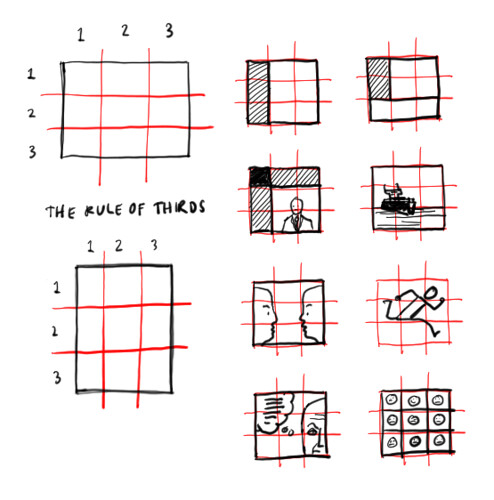

The rule of thirds

The rule of thirds is a principle of composition that helps you keep your images dynamic.

The rule of thirds is a principle of composition that helps you keep your images dynamic.

It gives you eight elements to work with — four lines and four intersections. Placing points of interest along the lines or at the intersections tends to create a more interesting composition.